George St-Pierre – The Way of the Fight

Mediocrity

As Aristotle wrote a long, long time ago, and I’m paraphrasing here, the goal is to avoid mediocrity by being prepared to try something and either failing miserably or triumphing grandly. Mediocrity is not about failing, and it’s the opposite of doing. Mediocrity, in other words, is about not trying. The reason is achingly simple, and I know you’ve heard it a thousand times before: what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. (p. 8)

Pick A Goal

pick a goal, make a realistic plan to reach that goal, work through each step of the plan, and repeat. (p. 12)

Learning From Losses

Some people learn to lose. Others lose and learn. The latter is a much better approach in my opinion because it focuses the mind on the positives and keeps your thoughts away from the negatives. One of my favorite Japanese proverbs is “Fall down seven times, stand up eight.” (p. 25)

Behaviour Depends On Situation

There’s me in a hostile environment, when I need to be hard and without pity, and then there’s me when I’m in relaxed surroundings. There’s quite a difference . . . At the end of high school, I stopped talking to people, stopped connecting and just focused on myself. I discovered a darker side, a darker place in my existence. I’m not sure exactly how to explain it. I just think it was part of my evolution. I’ve been a good and nice person at times, and it has helped me win opportunities, and other times I’ve been pitiless because that’s what the situation demanded of me. (p. 38)

Avoid Casual Repetition

I was making decisions. Train instead of party. Work instead of play. Perfect practice instead of casual repetition. (p. 40)

Gradual Improvement Over Time

One of the lessons I learned in all those years of practicing karate is that progress only comes in small, incremental portions. Nobody becomes great overnight. Nobody crams information if he wants to be able to use it over the long term. (pp. 71-72).

Think about climbing a mountain. If you decide you’re going up Everest, you don’t start with a sprint. You’ll never make it out of base camp if you do that. The secret is twofold: make sure your approach is consistent and steady so that you can maintain the progress you’re making as your journey continues. (pp. 73-74)

Randori

The kind of practice we participated in is called randori. Essentially, it means freestyle practice of one-on-one sparring. The goal is to resist and counter the opponent’s techniques. The Japanese translation of the word randori is “chaos-taking,” or “grasping freedom.” Well, they almost fought over me. I suffered my share of whoopings. I ate a lot of randori, let’s say. I was really discouraged at first, but I went there to learn Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, to learn the art of fighting on the ground from the experts. Those guys really are the best in the world. (p. 93)

Shootboxing

You need to practice the integration of wrestling, striking and kickboxing. (paraphrased)

Now, most people learn a little boxing, they learn a little wrestling, they learn a little Muay Thai, and they haphazardly patch them together. Then they hope for the best when they get into a mixed martial arts competition. That’s the extent of most people’s development. But the possession of great credentials in any one of the martial art components guarantees nothing in your ability to shootbox, or your ability to punch your way into a takedown. You can be a great boxer, yet be afraid to throw a punch in a shootbox—because you’re afraid of being taken down. You can be a great wrestler, but you can’t score a single great takedown—because you’re afraid of being punched in the face. And so on. Therefore, people can have what would appear to be outstanding credentials to make them a great shootboxer, and yet fail. (p. 121)

Front Foot Position

My front foot always points to my adversary. This is important because it stops my opponent from having or developing an angle on me. You can never allow that to happen because, quite simply, it exposes your blind side. It creates weakness. A fighter can’t afford to leave his flank or his blind side open, ever. Not addressing the opponent with your foot exerts a very negative influence on your power too. Misalignment reduces the power you can generate from one side of your body. So maybe you can throw a jab or a leg kick, but you make it very difficult to follow with a powerful combination from your strong side. In addition, you give the opponent more attack options while limiting your own angles and approaches. (p. 118)

Reading Opponents

My system is designed to read the other guy’s code; it’s designed to counter any attack coming my way, which complicates things for all my opponents. So first, what the heck is a fighting code?

Well, it doesn’t just exist in martial arts—it’s about the origins of all movements and how our minds respond to seeing them. In baseball, for example, you can tell someone’s going to swing the bat before the hands and arms even start moving to swing the bat—and that comes from looking at the hitter’s hips, or sometimes his eyes. Or in poker, a skill game based on your cards, and your opponent: if you are good enough, you can tell when another person is bluffing you, or trapping you. All it takes is for your eye to catch someone’s “tell,” his or her code. In any fighting art, a punch, kick or lunge has a beginning, a middle and an end. A jab, for example, starts on one side of the hips. So the code for a jab is a twitch in the hip.

When I watch my opponent, my mind automatically checks for all these signals, these codes, so that I can predict what’s coming. Each one of his tactics is connected to a code. This is why preparation and practice are so crucial in the lead-up to a fight: you practice being able to tell what the other guy is planning on doing, because one thing is for sure: your mind is faster than any part of your body, and it controls your reflex time.

This is crucial to my style of fighting, because everything I do is built on speed: recognition and reaction. Many of my takedowns, for example, actually come when most other fighters would be moving backward to avoid contact. But when my mind catches a signal that your right-hand lead is coming, I have trained myself to be ready to pounce forward and avoid contact. I dip my head to avoid the punch, I move my hand upward to ensure there’s no contact or damage, I dip my shoulder into your mid-waist area, and I try to take you down as fast as possible to gain an advantage and position. (p. 122)

Sparring

It all begins with training at very slow speeds. If you ever get a chance to visit Tristar Gym when I’m training, you can see me in the ring, boxing almost in slow motion without gloves on. My practice partner and I are taking turns throwing different punching and kicking combinations so we can recognize the code—we need to give our powerful brains the time to get used to the code. As we get warmer and better, and as our brains start developing better reaction times, we gradually speed up into full sparring mode. (p. 123)

Routine

I have a belief that all human greatness is founded upon routine, that truly great human behavior is impossible without this central part of your life being set up and governed by routine. All greatness comes out of an investment in time and the perfection of skills that render you great. And so, show me almost any truly great person in the world who exhibits some kind of extraordinary skills, and I’ll show you a person whose life is governed largely by routine. (p. 130)

Practicing A Single Technique

That’s why we get along—because John and I are both obsessively compulsive. We will spend hours repeating a single technique, over and over again until I get it right. We will repeat the move. We will sit and discuss it, then start over again. We will block out all other things. We will restart until the world dissolves completely. Until nothing else matters or even exists. We will repeat it until it is mastered, no matter when that will be. One certainty, though: it will be. (p. 130)

… Yet, many was the time that I would show a class a technique, and then I would go away and teach other classes back to back. I would look over at the far side of the academy and see Georges, still working that same technique, having gone through six or seven training partners because no one else could keep up with the intensity of his own training. (pp. 130-131)

… I have no choice, because there are two kinds of people who do martial arts: those who practice a thousand different kicks one time each, and those who practice one kick a thousand times minimum. (p. 131)

High Percentage Approach

And so the question arises: How will you control chaos? Why is it that when Georges St-Pierre is 22–2, most mixed martial artists are 10–10? Why are Georges and Anderson Silva nearly undefeated? What is different about these guys? How do they control such a chaotic situation? What I always advocated in my teaching of Georges is the high-percentage approach. Minimize the risk while maximizing the risk to your opponent. (p. 136)

Stances

The key for me was to understand the use of all fighting stances. Fighting stances meet and are are connected by an invisible thread. Your brain is the one that controls the thread and makes strategic choices. Broken down simply, here’s how my brain works it: take a boxer to the ground, keep a wrestler on his feet, and never waste energy in transition to try and bring someone to ground—it’s too tiring. Think about it. A specialist will use a lot of energy to bring you to his strength. Tactically, you have to manage this so that, even if you don’t end up in his strength area, his energy reserves are depleted compared to yours. I often let guys out of a hold because I don’t want to waste energy trying to keep them down while they just sit there, breathing, resting and thinking. (p. 137

Movement & Foot Position

I’d rather pick my spot than take one shot so I can try to deliver five in return. My body is my working tool and I don’t want to harm it, if possible. My favorite fighters are guys like Hopkins, who’s still fighting in his forties because he was able to control the big hits he took and minimize their long-term impact. He can roll with the punches. It’s all about absorption and constantly moving and staying out of the striking axis. Simply getting out of the way. Sometimes you take a shot, but not a direct shot. Roll, be fluid and never stay right in front of your opponent. (pp. 137-138)

Did you know that our toes and feet can keep our balance better than anything else? They keep us centered. Every single movement we make starts with our feet. Feet are the genesis of all movements, especially in mixed martial arts. It’s where most of our power comes from.

Think about it and try it: if your feet are not well positioned on the ground, how can you effectively change direction? If your base is not well positioned, you have to move one of your feet first, then apply pressure to generate movement, then move the other foot, and only then can you generate any kind of power or momentum. This sounds a lot like walking, I know. In the octagon, or on the basketball or tennis court, or when you’re running after a ball or trying to deke your opponent, walking isn’t the solution. It takes time and it wastes energy. By being in the right position to begin with, you save time and energy, and you maximize power. (pp. 152-153)

The elementary truth is that feet are all about posture; they determine how you carry yourself. They play a role, whether you slouch or stand upright with your shoulders rolled back. (p. 155)

Keep Moving

To me, Georges is an ant. Everything he does can be compared to ants and how they live, what their existence is about. First of all, Georges is always going somewhere. He always has a place to go. He never stops moving, he never stops doing things that will get him closer to his goal, no matter what. And that’s because he’s part of a greater idea. (p. 158)

Strengths and Weaknesses

What happens when you accept and embrace your fear? Fear becomes your weapon. Some people are totally incapable of seeing fear as an opportunity to get better at something. To develop the best version of themselves. (p. 162)

The big lesson here is this one: fight his weaknesses and avoid his strengths. (p. 176)

Mindset

“You don’t get better on the days when you feel like going. You get better on the days when you don’t want to go, but you go anyway.” (p. 178)

Rest

But I’d been working out less than before. It makes me feel so dumb for all the years I did things wrong. Now I know: resting is growing. (p. 187)

Train With Resisting Opponents

There are times when hitting the bags is important, but those decrease in importance as my expertise grows. Bruce Lee talked about this a lot. Hitting the bags or the dummies is good to create muscle memory while I’m trying to perfect a movement—a punch or a kick. But it means nothing else. Once I learn a movement or a style of kick well, I need to perform it against a willing opponent. (p. 187)

Luck and Movement

Knowing yourself lets you differentiate between luck and movement. It places them at opposite ends of the spectrum. Luck is not within anybody’s control or prediction. It occurs, and it’s great when it does, but you can’t base your entire life on it. Movement, on the other hand, puts success within reach. The more you know about yourself, the better your movement through all facets of life. (p. 191)

Stick with It: The Science of Lasting Behaviour

Notes and text from: Young, Sean. Stick with It: The Science of Lasting Behaviour. Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

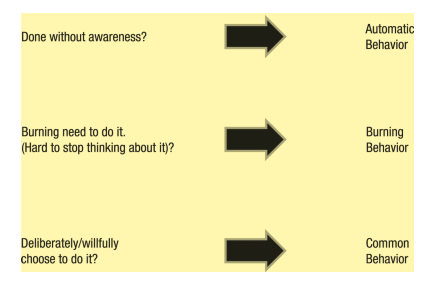

First identify the type of behaviour your looking to change:

• Automatic – we do it with out thinking.

• Burning – We feel a strong desire like we have to do it.

• Common – We are aware of what we are going and still want to do it, even when we no it is bad for us.

The difference is the extent to which people are mindful of their behavior— or realize what they’re doing at the time— and therefore are able to stop it.

The difference between A, B, and C behaviors lies in how much conscious control people have over them. In general, the more conscious thought goes into a behavior, the easier it is to change.

The problems are different because one of them is done consciously the other is done unconsciously. That also determines what forces should be used to stop them. Take a resolution to keep good posture, compared to one to exercise daily. People often start slouching or lose good posture unconsciously, without their awareness. That makes it difficult to apply certain forces to keeping good posture— for instance Stepladders, which would have people plan small, gradual steps. If you’re not even aware that you’re slouching when you’re doing it, it’s difficult to take small steps to stop doing it. Getting yourself motivated to exercise is a different type of problem, though. People are often aware of what they’re doing when they want to get themselves to exercise. They just need more motivation to do it at that moment. Forces like Stepladders can be helpful here. A person could take the first step of going for a two-minute walk. The difference in which forces to use depends on people’s awareness when they’re doing something they want to change and how capable they are of changing it.

First, as a general rule, people will be more likely to follow through with things if they use as many of the seven forces of lasting change as they can. But the second thing is that not all seven forces are always needed: knowing when and how to use the seven forces will lead to greater follow-through.

The problems are different because one of them is done consciously the other is done unconsciously. That also determines what forces should be used to stop them.

Take a resolution to keep good posture, compared to one to exercise daily. People often start slouching or lose good posture unconsciously, without their awareness. That makes it difficult to apply certain forces to keeping good posture— for instance Stepladders, which would have people plan small, gradual steps. If you’re not even aware that you’re slouching when you’re doing it, it’s difficult to take small steps to stop doing it. Getting yourself motivated to exercise is a different type of problem, though. People are often aware of what they’re doing when they want to get themselves to exercise. They just need more motivation to do it at that moment. Forces like Stepladders can be helpful here. A person could take the first step of going for a two-minute walk. The difference in which forces to use depends on people’s awareness when they’re doing something they want to change and how capable they are of changing it.

First, as a general rule, people will be more likely to follow through with things if they use as many of the seven forces of lasting change as they can. But the second thing is that not all seven forces are always needed: knowing when and how to use the seven forces will lead to greater follow-through.

Automatic

An automatic behavior is something that people do without conscious awareness. It is almost impossible for us to stop ourselves when we’re doing automatic behaviors because we’re not aware we’re doing them. Automatic behaviors happen automatically, often under the same situations, or conditions. For that reason, one of the ways to change automatic behavior is to use conditioning.

Because people aren’t aware when they’re doing something automatically, it won’t work to use forces that require people to be conscious of what they’re doing when they’re trying to change.

In short, if you want to change automatic behaviors, use Easy and Engrained. If possible, also use Neurohacks and Captivating. It won’t really help (or hurt) to use the other forces designed for changing behaviors that are more conscious.

Automatic Behaviors. Automatic behaviors are done without much thought. There are a specific set of forces needed to address automatic behaviors because they happen without awareness. The more stars, the more important that force is needed to change the behavior.

Burning

A burning behavior is a feeling of having an irresistible urge, or burning, to do something. Although automatic behaviors are the most firmly engrained behaviors because people do them automatically and typically without awareness, burning behaviors are the second most engrained behaviors because they are thoughts that feel impossible to not act on. People might feel like they can’t stop themselves from following through with burning behaviors, but the ability to at least be aware of when they’re engaging in them is what makes them different from automatic (no awareness) behaviors.

An addiction, craving, or obsession such as needing to have a cigarette or to check email is often an example of a burning behavior. Just as addictions can be rooted biologically in the brain, the repetitive and uncontrollable thoughts and urges from burning behaviors can be so strong that it is very tough to not act on them. Then why aren’t they automatic behaviors? Because while the unconscious nature of automatic behaviors means that people can’t stop themselves from doing them, people can stop themselves from doing burning behaviors.

Burning behaviors are almost, but not quite, automatic, meaning that very similar forces are needed to change burning and automatic behaviors (Easy, Neurohacks, Captivating, and Engrained). But because people are also aware when they’re doing something that’s a burning behavior, other forces that require awareness are also helpful.

Automatic and Burning Behaviors. Compared to automatic behaviors, people are more aware of what they’re doing during burning behaviors. I show this by putting part of a brain inside the person with a burning behavior while the person with an automatic behavior does not have a brain (this is for illustration purposes, as everyone has a brain!).

Common

Common behaviors are things that people do repeatedly and consciously, at least part of the time they’re doing them. An example of a common behavior could be coming home from work and grabbing a handful of unhealthy snacks instead of waiting for dinner. A person might be aware that they’re eating the snacks but that’s not enough to get them to stop.

Compared to automatic behaviors and burning behaviors, people are more conscious of what they’re doing during common behaviors. Common behavioral problems feel like they’re due to lack of motivation, such as being too tired to meet up with friends and instead falling back on the familiar routine of answering emails. Common behaviors don’t occur unconsciously, so we need more than the forces that are used for automatic, unconscious behaviors.

Changing common behaviors requires using more forces designed for when people are aware of what they’re doing.

In general, to create or change common behaviors, people should use as many of the seven forces as they can.

Then decide what tools to use to change behaviour

Changing behaviour is more complicated than just applying will power. The type of behaviour will determine the type of tools/actions you should take to change behaviour. These tools are additive and work more effectively when used in combination rather than isolation.

1. Stepladders. Take a tiny step. Really small. Be prepared to aim lower but still up.

The lesson is to focus on finding the right first step. Put all of your energy into achieving that first little step. Take the time to reflect on your progress. And then repeat.

People might know intellectually that they should take small steps toward their goal, but they still plan steps that are too big. There’s a reason for this. It’s hard to get excited about planning little steps. It’s much more exciting to dream big.

For example, you could either make a resolution to lose ten pounds before a wedding next month, or you could plan to go to the gym today. How exciting is it to make a resolution to go to the gym today? Not very. If you’re trying to shed a bunch of weight, then going to the gym one day doesn’t sound impressive. It’s not like you’ll look any different afterward. It’s more exciting to dream of losing every hated pound and making everyone’s jaw drop as you walk into the reception hall.

But focusing entirely on achieving big, long-term dreams can actually have the reverse effect— people can become discouraged and quit because the dreams are too big and too far in the future.

People think they are taking small steps but they are not small enough. After all the concept of small is subjective.

People need to be reminded of their dreams to keep them motivated, but focusing entirely on dreams can lead people to give up. Instead, people should focus most of their energy trying to complete steps and goals. Goals are the intermediate plans people make. There are short-and long-term goals. Long-term goals typically take one month to three months to achieve, like learning the basics of a new language. A long-term goal could take more than three months to achieve, but only if it’s something you’ve already done before; otherwise it’s a dream.

Finally, there are steps. Steps typically take less than one week to accomplish. Steps are the little tasks to check off on the way toward a goal.

It intertemporal choice or delay discounting: people assign greater value to smaller, quick rewards over larger, more delayed rewards… Focusing on small steps allows people to achieve their goals faster than if they focused on dreams.

Studies continue to show that people should focus more on their shorter-term goals rather than longer-term dreams.

The other essential ingredient of stepladders is reflection. Reflection is the act of looking back on a successfully completed behaviour and having a small celebration.

2. Community. It is easier to succeed if the people around you are supporting you and going in the same direction.

Be around people who are doing what you want to be doing. Social support and social competition foster change.

Every successful community has six ingredients that address people’s psychological needs. They are; trust, people fit in, it provides self worth – people feel good about themselves, provides rewards, has a social magnet, makes people feel empowered.

3. Important.

So what are the things that researchers have found are important to people? The three top ones are money, social connections, and health.

An action has to be important enough to an individual to make them act. What is important will vary from person to person. Typically, you will emotionally feel things that are really important to you.

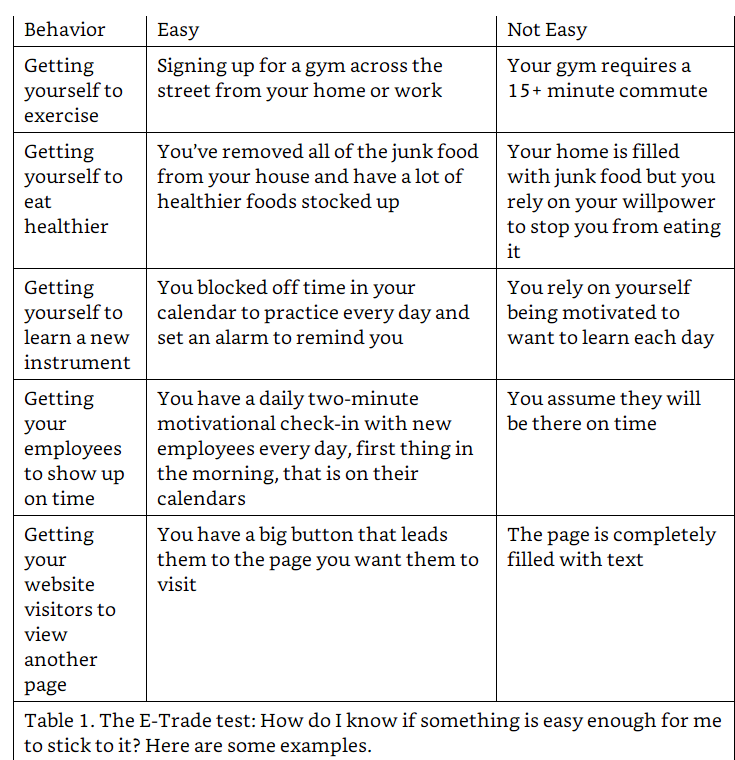

4. Easy. The easier it to do something the more likely we are to do it. Conversely, we are less likely to do hard things. So make it harder to do negative things and easier to do positive things.

This might include things like reducing choice to fewer options or placing barriers in the way of other options. Controlling the environment greatly impacts what is easy.

One reason is that people have too many choices. 13 The science of “choice paralysis” isn’t limited to romantic partners, though. It also explains why people find it tough to do almost anything in life, whether it’s going for a run, going to sleep early, or calling grandma to say hi.

When you give people a smaller number of choices, it becomes easier for them to make a decision to do something, and to keep doing it. Although people think they want to have a lot of choices, too many choices actually makes it tough for people to do things.

Have a clear step by step plan of what to do makes things clear and easy. This can include checklists. Providing people with the exact information they need can also make it more likely they will follow these steps.

Easy to do means more likely to do.

People don’t just make things too complicated for others, however; they also overcomplicate things for themselves, which makes them less likely to follow through with their own plans. People sign up for gyms that are far away from their homes. They like the gym and think they’ll be able to keep going, but it’s not easy to keep going so they quit.

5. Neurohacks. Change your actions and your mind will follow.

Conventional wisdom has it backward: lasting behavior change doesn’t typically start with the mind telling the body to make lasting change; it starts by making a small change in behavior and letting the mind reflect on that change.

Your past behavior shows that you complete your work before taking a break, and you need to remain consistent with that self-image of getting the job done before you play. Similarly, the answer to whether a person sticks it out for another ten minutes on her run or keeps sober another day depends on how she thinks of herself after looking back at past behavior. If her past behavior signals she’s a fighter, then she’ll want to maintain that self-image and stick it out and fight.

Neurohacks get people to stick with things through two psychological processes: 1) people convince themselves that if they’re doing something without being pressured to do it, it must be because it’s important to them (people will then stick with that behavior to remain consistent with what’s important to them) and 2) people form an identity of themselves by looking back on things they’ve done in the past (people will continue doing that behavior because it is part of their self-image).

I define neurohacks as psychological tricks that get people to reset their brains by looking back on their past behavior.

This could include tricks like changing your password to something like Quite@smoking etc. Forcing behaviour change leads to mental change and then change of actions.

6. Captivating. Make a behaviour engaging enough that people want to keep doing it.

The idea is simple. People will keep doing things if they feel rewarded for doing them. I call this the captivating element of sticking to a behavior.

We are simply conditioned to behave in a certain way. If consequences of doing something are bad, then we don’t do it again. If consequences are good, we will repeat the action or behavior.

The reward needs to be truly captivating! For that reason, we don’t call this chapter “Rewarding.” We want to separate captivating rewards from the typical advice that simply handing out rewards for an action is sufficient to get someone to stick to something. The difference between “just any reward” and something that is truly captivating is the difference between someone doing something once and feeling compelled to keep doing it.

The difference between any reward and a captivating reward lies in whether the reward is important to the person.

Although fear can motivate people to do things for a little while, research shows that it’s not sustainable.

A study of “fear” literature showed that although fear could appear to motivate people to change their behavior for the short term, in the long term it simply scares them into reactive mode by triggering avoidance of the topic in question as well as denial.

If you give a large reward to people for doing things they already enjoy doing, they’ll often lose their motivation to keep doing them. 21 22 Think carefully before you increase the salary of an employee who already loves what he does. It might reset his brain to stop thinking of the work as pleasurable and start thinking of it as a tedious task that requires a lot of compensation to keep people motivated.

However, like negative fearmongering, simply handing out rewards does little but encourage “temporary compliance” with a course of action. The fact is, the activity itself has to be rewarding.

This is a subtle but important difference. Research has shown repeatedly that once the rewards stop flowing, people’s behaviors will revert to what they were before. They are extrinsic, not intrinsic, to what commits us to act in certain ways.

However, the survey found that training and goal-setting programs affected worker productivity to a far greater extent than so-called pay-for-performance plans.

The Quick Fix is the immediate reinforcement people need for doing something. If you just entered a casino, immediately hearing the clanging of coins dropping out of a winning slot machine is an example of a Quick Fix. It immediately teaches people that they can win, too— and that they should keep walking in, put some money down, and let it roll. An important thing about the Quick Fix is that people need to get it quickly after they start something. If it takes a while to get the Quick Fix— making it no longer quick— then people won’t connect the reward to the behavior.

The reward also needs to be appropriate for people to keep doing something. A leaderboard of “top employees” isn’t an appropriate reward for an employee who is motivated by supporting coworkers rather than competing with them.

The “Trick Fix” involves intermittent reinforcement. The science behind this goes back to B. F. Skinner, who discovered that rats that were intermittently rewarded with pellets by pushing a lever would push the lever more frequently than rats that were always rewarded. In effect, you’re “weaning” yourself off the reward by getting it when you don’t expect it. So once you feel that you’re on a good path to sticking to something, gradually taper off your reward.

The process should be immediately rewarding to be truly effective.

If you can understand the difference between giving just any reward compared to one that you or someone else truly finds captivating, then you’ll have the power to make change stick.

7. Engrained (Habits). Habits makes doing a task easier and requiring less effort. This comes from repetition.

The human brain is amazingly efficient. It is designed so people can do things without having to think. It rewards people for sticking to routines.

Brains are like cars. Driving them in manual mode takes a lot of awareness and effort. But brains prefer to be in automatic mode. They do this by storing things that frequently occur so they can be easily accessed. Think of it like your computer storing your username and password for a site you visit often. That way, you can log in effortlessly, without thinking, allowing you to concentrate on other things.

That habit then becomes a go-to default behavior. The bad news is that habits— such as addiction to drugs— can be destructive and exceedingly hard to change. The good news is that, with the right efforts, undesirable patterns can be changed. And once people change their habits, strong forces will then be in place to make the new behavior last.

I use the word engrain to describe the process the brain uses to create lasting change. When the brain believes it needs to remember information or a behavior— usually because the thing happens repeatedly— the brain engrains that information or behavior to make it easy to remember so it can do it again.

Because the brain wants to be hyperefficient, it doesn’t stop there. In addition to engraining information about sounds, smells, and sights, the brain also engrains what people do repeatedly. If you take the same route to work each day, the brain encodes this information so you can easily take the same route again. The more you take that route to work, the more it becomes engrained and the less you have to think about how to get to work. The brain follows this pattern across all things in life, even for things that we are not aware of seeing or doing.

The secret to making things engrained in the brain is based on this repetition: repeating behaviors, especially if it can be done every day, in the same place, and at the same time, will teach the brain that it needs to remember this behavior to make it easier to keep doing it. It will engrain this behavior.

One of the secrets to this is repetition. This can be enhanced by doing things at the same time in the same way.

People can pair similar behaviors together so that if they get themselves to do one thing they can easily do, then it will make them more likely to do the other thing that is hard to do. For example, a person might have trouble motivating himself or herself to go for a daily run but can pair this with something he or she already does on a daily basis, like putting on shoes.

Think about it. Because we already put shoes on every day, it is already engrained in our brains. Without much effort, we can substitute the typical work or casual shoes we put on with running shoes. Because running shoes are automatically paired with running, we find it increasingly easier to run. I call this a magnetic behavior because doing one behavior (putting on running shoes) can be a magnet that causes another related and desired behavior (running) to occur.

Sticking with that easy-to-do routine that has led to his success in the past helps him follow through and reach similar success in the future.

To learn a new behavior, researchers found that animals need a stimulus (or a trigger), a response (the behavior), and then a reinforcement (a reward that would make the animal want to do it again).

So why doesn’t conditioning (or habit science) work to create lasting behaviors? If conditioning were the only solution needed for behavior change, then why would this book spend only a few pages of the Captivating chapter teaching you about conditioning?

Obviously it’s because I don’t think it’s the only solution. And neither do most scientists in the field of psychology. In fact, many psychologists think the field of behaviorism is dead. 10 Why? First, people aren’t caged animals, so the research on conditioning that was done on animals often doesn’t apply because people’s minds and lives are more complicated than animals. Second, not all behaviors are the same. There are different types. Each type of behavior requires a different set of forces to change it. Captivating is one tool, but we need more than one tool in our toolkit to make behaviors stick.

Take going running a few times a week. You can’t use conditioning to make that a “habit,” because it will never be a quick, automatic, and unconscious behavior. People have to consciously go through a number of steps to go for a run. When is the last time you realized you had gone for a run without thinking about it?

Although individual parts of this process could become habits— like a few minutes in the middle of the run when the body is automatically moving and the mind begins to wander— the larger process is not a habit.

Firas Zahabi Interview – Joe Rogan

How To Workout Smarter – Summary

The Unfinished Work Week

86% of a person remembers is seen as opposed to 9% being heard. We should therefore focus more on visual communication. This is seen in the fact that most people process only 7 verbal bits (or 4 if you take into account modern distractions) of information in 30 seconds but can process 15 bits of visual communication in the same time.

The author suggests that the visual learning is much greater than verbal learning. We should therefore use more visual learning to communicate than we do.

The average person reads 250 words a minute but they can not comprehend this level of information. Therefore we tend to scan or miss things. The average email has 100 words and so is read in 25 seconds. But it likley that you can only comprehend only 45 words in these 25 seconds.

There are three types of attention.

- Controlled Attention – actively decide to concentrate on some thing.

- Stimuli Attention – an involentary response to simuli such as a phone ringing or an email arrving. You must contiously re-establish controlled attention to get the most from your memory process.

- Arousal attention – the loss of attention when a topic becomes monotonous and boring.

Jocko / Jordan Peterson Podcast – Notes

Discusses leadership and how try to beat people to do something is a waste of energy. The team of people who are motivated to move in the right direction with out this threat because their interests are aligned with yours will beat the forced pushed group of people facing them. It is a waste of energy and time to monitor and control people. It is much better to get people willingly moving the same way you are. People who are forced to do things sabotage. They do half assed jobs. You never get their full commiment.

Additionally it discussed how you need to connect all the dots and make them understand why your goals serve their life goals. So more profits for the company isn’t motivating unless the worker understands this leads to bigger bonuses for them or helps grow the company and so creates opportunities for them to move up in the hierarchy.

The Outsiders – Notes

- The CEOs most important job is capital allocation

- Enphasising free cash flow was the key to long term value creation. As it freed cash to be invested in the highest return investments either internallty or externally.

- Net income is a blunt tool for measuring business performance as it can be distorted by differences in debt levels, capital expenditure and aquistion history.

- CEOs need to run their opperations effectively and deploy the cash generated by those opperations.

- The most successful CEOs decentralised opportations and centralised capital allocation.

- CEOs have five basic choices for capital allocation: aquireing other businesses, issuing dividences, paying down debt, repurchasing stock. And three ways of raising capital, tapping internal cash flow, issuing debt and raising equity.

- What matters in the long run is increase in per share value, not overall growth or size.

- Cashflow, not reported earnings determines long term value.

- Decentralised organisations keep both costs and rancor down.

- Indpendant thinking is essential to success. Interactions with outside advisors can be distracting and time consuming.

- With aquistions waiting for the right deal is a virtue. As is occational acts of boldness.

- The top CEOs did simple one or two pay calculations themselves rather than relying on other peoples estimates. They used conservative esitmates.

- The most successful CEOs were value buyers who had simple rules (eg 5 x cashflow) that were easily quantifiable, when buying. They would not break their rules even for modest differences in price.

- They used their own shares to buy other businesses when they felt they were overvalued and purchases their own shares (in bulk no gradually) when undervalued.

- Use of leases on cinmea purchases decreased the amount of capital employed in the new cinema locations.

- The best investors looked for “no brainers” rather than just good investments. They wanted investments with a “margin of safety”. That was investments with an important competitive advantage and a price well below the intrinsivc value (the price a fully informed, sophisitcated investor would pay for the company).

- Many of the purchases of companies were made directly rather than when the companies were on the open market and competition for them was higher.

- Companies with low capital needs and the ability to raise prices were best placed to avoid the corosive impact of inflation.

- Charlie Munger attributed his and Warren Buffets success to the ability to “raise funds at 3% and invest them at 13%”.

- The most succesful CEOs “believed what mattered was clear-eyed decision making, and in their cultures enphasised seemingly old-fashioned values of frugality and patience, independance, and (occational) boldness, rationality and logic. P209

- They often had very small offices and central administration. There seemed to be a inverse relationship between how expensive the company headquaters was and investor returns.

- These investors were will to wait seemingly indefinately when returns were uninteresting.

- Always do the maths to make sure every investment decision is the best option available. The maths is simple but most people don’t do it they just focus on their prefered project and don’t consider alternatives. Choosing from a wider range of alternative increases your likely return. Focusing on a wide range rather than just with in your current industry is a form of competitive advantage over people who fail to do this.

- “Float” is money that you control but don’t own. Warren Buffet controls billions in insurance premiums that may take years before they pay out. This allows low cost investing. This can be done with the money owed to suppliers via cashflow. But avoiding low profit (pricing) options and waiting for high profit (price) options means cash is available for these “no brainer” investments when you see them.

The Marshmallow Test Notes

“self-control is like a muscle: when you actively exert volitional effort, “ego depletion” occurs, and the muscle soon becomes fatigued. Consquently, your willpower and ability to overide impulsive behaviour will temporarily diminish on a wide variety of tasks that demand self control.” P 216/7

“The motivational interpretation of effortful persistance simply argues that mind sets, self standards, and goals guide when we will become invigorated rather than drained by our efforts, and when we need to relax, nap and self reward” P 219

We need to cool our immediate impulses and heat the later “push thetemptation in front of you far away in space and time, and bring the distant consquences closer in your mind” P256

The Self Made Billionaire Notes

“Changes came quickly, but they were based on direct engagement with customers.” P 82

Billionaires are no more inclined towards risk than the average person. The cliche of the entreprenurial risk taker is not true. Instead billionaires do not over value what they already have and over wiegh the risks that they are taking. These are both tendencies of the average person. Billionaires do not take irrational risks they just see the risks more clearly and objectively not placing excessive weight to their view of risks. (P119 / 120 paraphrased)

Billionaires often have parrel streams of income so they do not have all their eggs in one basket. (P128 Paraphased)

“their definition of risk, is one that in the event of failure, to dust off and start again” P131 In other words billionaires are more resiliaiant. They often don’t truely succeed until their third or fourth business.

“You can try and fail a hundred times , but you only have to get it right once” MArk Cuban P135

Lead and Lag Indicators

When tracking movement towards an objective we can look at either lead or lag indicators. If we were trying to lose weight we could measure our weight every week. This would be a lag indicator that would tell us if our efforts had been successful or not. Alternatively we could track the calories we consumed each day. This would be a lead indicator. Making sure we conformed to certain requirements would tell us if we were taking the actions that would result in our desired outcome. Looking at lead indicators is often more effective as your daily activity and therefore your movement towards the goal. Lag indicators are useful and should be used as well but they tell you after thing have already happened. The results from a lag indicator might be the consquence of actions that were taken perhaps a few weeks previously. It is therefore less clear what actions actually caused the outcome you recieve.