Notes and text from: Young, Sean. Stick with It: The Science of Lasting Behaviour. Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

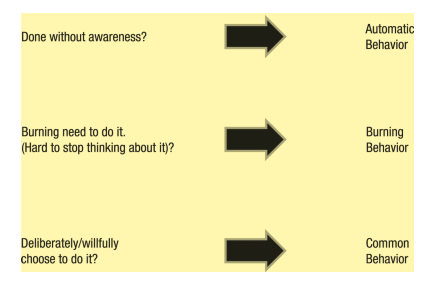

First identify the type of behaviour your looking to change:

• Automatic – we do it with out thinking.

• Burning – We feel a strong desire like we have to do it.

• Common – We are aware of what we are going and still want to do it, even when we no it is bad for us.

The difference is the extent to which people are mindful of their behavior— or realize what they’re doing at the time— and therefore are able to stop it.

The difference between A, B, and C behaviors lies in how much conscious control people have over them. In general, the more conscious thought goes into a behavior, the easier it is to change.

The problems are different because one of them is done consciously the other is done unconsciously. That also determines what forces should be used to stop them. Take a resolution to keep good posture, compared to one to exercise daily. People often start slouching or lose good posture unconsciously, without their awareness. That makes it difficult to apply certain forces to keeping good posture— for instance Stepladders, which would have people plan small, gradual steps. If you’re not even aware that you’re slouching when you’re doing it, it’s difficult to take small steps to stop doing it. Getting yourself motivated to exercise is a different type of problem, though. People are often aware of what they’re doing when they want to get themselves to exercise. They just need more motivation to do it at that moment. Forces like Stepladders can be helpful here. A person could take the first step of going for a two-minute walk. The difference in which forces to use depends on people’s awareness when they’re doing something they want to change and how capable they are of changing it.

First, as a general rule, people will be more likely to follow through with things if they use as many of the seven forces of lasting change as they can. But the second thing is that not all seven forces are always needed: knowing when and how to use the seven forces will lead to greater follow-through.

The problems are different because one of them is done consciously the other is done unconsciously. That also determines what forces should be used to stop them.

Take a resolution to keep good posture, compared to one to exercise daily. People often start slouching or lose good posture unconsciously, without their awareness. That makes it difficult to apply certain forces to keeping good posture— for instance Stepladders, which would have people plan small, gradual steps. If you’re not even aware that you’re slouching when you’re doing it, it’s difficult to take small steps to stop doing it. Getting yourself motivated to exercise is a different type of problem, though. People are often aware of what they’re doing when they want to get themselves to exercise. They just need more motivation to do it at that moment. Forces like Stepladders can be helpful here. A person could take the first step of going for a two-minute walk. The difference in which forces to use depends on people’s awareness when they’re doing something they want to change and how capable they are of changing it.

First, as a general rule, people will be more likely to follow through with things if they use as many of the seven forces of lasting change as they can. But the second thing is that not all seven forces are always needed: knowing when and how to use the seven forces will lead to greater follow-through.

Automatic

An automatic behavior is something that people do without conscious awareness. It is almost impossible for us to stop ourselves when we’re doing automatic behaviors because we’re not aware we’re doing them. Automatic behaviors happen automatically, often under the same situations, or conditions. For that reason, one of the ways to change automatic behavior is to use conditioning.

Because people aren’t aware when they’re doing something automatically, it won’t work to use forces that require people to be conscious of what they’re doing when they’re trying to change.

In short, if you want to change automatic behaviors, use Easy and Engrained. If possible, also use Neurohacks and Captivating. It won’t really help (or hurt) to use the other forces designed for changing behaviors that are more conscious.

Automatic Behaviors. Automatic behaviors are done without much thought. There are a specific set of forces needed to address automatic behaviors because they happen without awareness. The more stars, the more important that force is needed to change the behavior.

Burning

A burning behavior is a feeling of having an irresistible urge, or burning, to do something. Although automatic behaviors are the most firmly engrained behaviors because people do them automatically and typically without awareness, burning behaviors are the second most engrained behaviors because they are thoughts that feel impossible to not act on. People might feel like they can’t stop themselves from following through with burning behaviors, but the ability to at least be aware of when they’re engaging in them is what makes them different from automatic (no awareness) behaviors.

An addiction, craving, or obsession such as needing to have a cigarette or to check email is often an example of a burning behavior. Just as addictions can be rooted biologically in the brain, the repetitive and uncontrollable thoughts and urges from burning behaviors can be so strong that it is very tough to not act on them. Then why aren’t they automatic behaviors? Because while the unconscious nature of automatic behaviors means that people can’t stop themselves from doing them, people can stop themselves from doing burning behaviors.

Burning behaviors are almost, but not quite, automatic, meaning that very similar forces are needed to change burning and automatic behaviors (Easy, Neurohacks, Captivating, and Engrained). But because people are also aware when they’re doing something that’s a burning behavior, other forces that require awareness are also helpful.

Automatic and Burning Behaviors. Compared to automatic behaviors, people are more aware of what they’re doing during burning behaviors. I show this by putting part of a brain inside the person with a burning behavior while the person with an automatic behavior does not have a brain (this is for illustration purposes, as everyone has a brain!).

Common

Common behaviors are things that people do repeatedly and consciously, at least part of the time they’re doing them. An example of a common behavior could be coming home from work and grabbing a handful of unhealthy snacks instead of waiting for dinner. A person might be aware that they’re eating the snacks but that’s not enough to get them to stop.

Compared to automatic behaviors and burning behaviors, people are more conscious of what they’re doing during common behaviors. Common behavioral problems feel like they’re due to lack of motivation, such as being too tired to meet up with friends and instead falling back on the familiar routine of answering emails. Common behaviors don’t occur unconsciously, so we need more than the forces that are used for automatic, unconscious behaviors.

Changing common behaviors requires using more forces designed for when people are aware of what they’re doing.

In general, to create or change common behaviors, people should use as many of the seven forces as they can.

Then decide what tools to use to change behaviour

Changing behaviour is more complicated than just applying will power. The type of behaviour will determine the type of tools/actions you should take to change behaviour. These tools are additive and work more effectively when used in combination rather than isolation.

1. Stepladders. Take a tiny step. Really small. Be prepared to aim lower but still up.

The lesson is to focus on finding the right first step. Put all of your energy into achieving that first little step. Take the time to reflect on your progress. And then repeat.

People might know intellectually that they should take small steps toward their goal, but they still plan steps that are too big. There’s a reason for this. It’s hard to get excited about planning little steps. It’s much more exciting to dream big.

For example, you could either make a resolution to lose ten pounds before a wedding next month, or you could plan to go to the gym today. How exciting is it to make a resolution to go to the gym today? Not very. If you’re trying to shed a bunch of weight, then going to the gym one day doesn’t sound impressive. It’s not like you’ll look any different afterward. It’s more exciting to dream of losing every hated pound and making everyone’s jaw drop as you walk into the reception hall.

But focusing entirely on achieving big, long-term dreams can actually have the reverse effect— people can become discouraged and quit because the dreams are too big and too far in the future.

People think they are taking small steps but they are not small enough. After all the concept of small is subjective.

People need to be reminded of their dreams to keep them motivated, but focusing entirely on dreams can lead people to give up. Instead, people should focus most of their energy trying to complete steps and goals. Goals are the intermediate plans people make. There are short-and long-term goals. Long-term goals typically take one month to three months to achieve, like learning the basics of a new language. A long-term goal could take more than three months to achieve, but only if it’s something you’ve already done before; otherwise it’s a dream.

Finally, there are steps. Steps typically take less than one week to accomplish. Steps are the little tasks to check off on the way toward a goal.

It intertemporal choice or delay discounting: people assign greater value to smaller, quick rewards over larger, more delayed rewards… Focusing on small steps allows people to achieve their goals faster than if they focused on dreams.

Studies continue to show that people should focus more on their shorter-term goals rather than longer-term dreams.

The other essential ingredient of stepladders is reflection. Reflection is the act of looking back on a successfully completed behaviour and having a small celebration.

2. Community. It is easier to succeed if the people around you are supporting you and going in the same direction.

Be around people who are doing what you want to be doing. Social support and social competition foster change.

Every successful community has six ingredients that address people’s psychological needs. They are; trust, people fit in, it provides self worth – people feel good about themselves, provides rewards, has a social magnet, makes people feel empowered.

3. Important.

So what are the things that researchers have found are important to people? The three top ones are money, social connections, and health.

An action has to be important enough to an individual to make them act. What is important will vary from person to person. Typically, you will emotionally feel things that are really important to you.

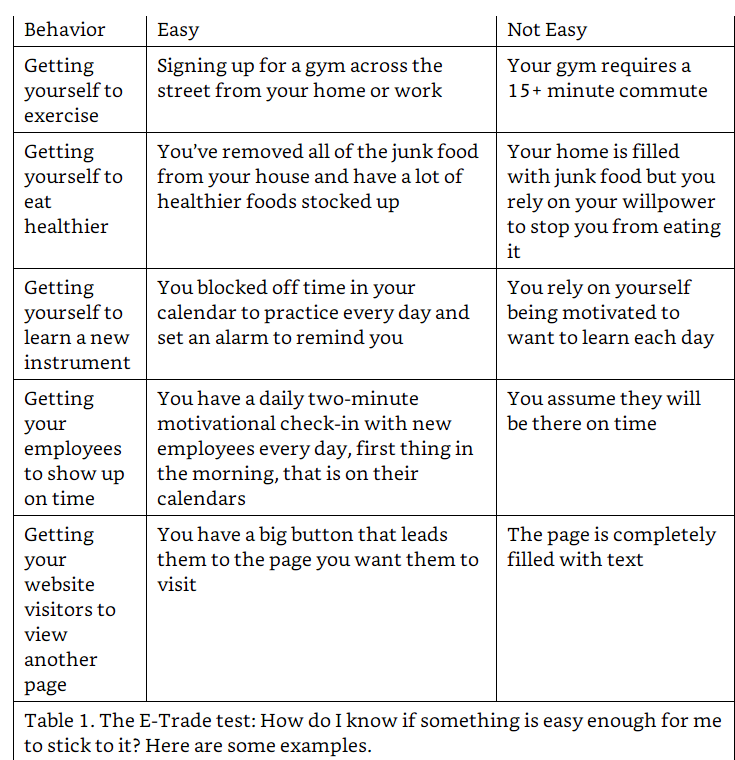

4. Easy. The easier it to do something the more likely we are to do it. Conversely, we are less likely to do hard things. So make it harder to do negative things and easier to do positive things.

This might include things like reducing choice to fewer options or placing barriers in the way of other options. Controlling the environment greatly impacts what is easy.

One reason is that people have too many choices. 13 The science of “choice paralysis” isn’t limited to romantic partners, though. It also explains why people find it tough to do almost anything in life, whether it’s going for a run, going to sleep early, or calling grandma to say hi.

When you give people a smaller number of choices, it becomes easier for them to make a decision to do something, and to keep doing it. Although people think they want to have a lot of choices, too many choices actually makes it tough for people to do things.

Have a clear step by step plan of what to do makes things clear and easy. This can include checklists. Providing people with the exact information they need can also make it more likely they will follow these steps.

Easy to do means more likely to do.

People don’t just make things too complicated for others, however; they also overcomplicate things for themselves, which makes them less likely to follow through with their own plans. People sign up for gyms that are far away from their homes. They like the gym and think they’ll be able to keep going, but it’s not easy to keep going so they quit.

5. Neurohacks. Change your actions and your mind will follow.

Conventional wisdom has it backward: lasting behavior change doesn’t typically start with the mind telling the body to make lasting change; it starts by making a small change in behavior and letting the mind reflect on that change.

Your past behavior shows that you complete your work before taking a break, and you need to remain consistent with that self-image of getting the job done before you play. Similarly, the answer to whether a person sticks it out for another ten minutes on her run or keeps sober another day depends on how she thinks of herself after looking back at past behavior. If her past behavior signals she’s a fighter, then she’ll want to maintain that self-image and stick it out and fight.

Neurohacks get people to stick with things through two psychological processes: 1) people convince themselves that if they’re doing something without being pressured to do it, it must be because it’s important to them (people will then stick with that behavior to remain consistent with what’s important to them) and 2) people form an identity of themselves by looking back on things they’ve done in the past (people will continue doing that behavior because it is part of their self-image).

I define neurohacks as psychological tricks that get people to reset their brains by looking back on their past behavior.

This could include tricks like changing your password to something like Quite@smoking etc. Forcing behaviour change leads to mental change and then change of actions.

6. Captivating. Make a behaviour engaging enough that people want to keep doing it.

The idea is simple. People will keep doing things if they feel rewarded for doing them. I call this the captivating element of sticking to a behavior.

We are simply conditioned to behave in a certain way. If consequences of doing something are bad, then we don’t do it again. If consequences are good, we will repeat the action or behavior.

The reward needs to be truly captivating! For that reason, we don’t call this chapter “Rewarding.” We want to separate captivating rewards from the typical advice that simply handing out rewards for an action is sufficient to get someone to stick to something. The difference between “just any reward” and something that is truly captivating is the difference between someone doing something once and feeling compelled to keep doing it.

The difference between any reward and a captivating reward lies in whether the reward is important to the person.

Although fear can motivate people to do things for a little while, research shows that it’s not sustainable.

A study of “fear” literature showed that although fear could appear to motivate people to change their behavior for the short term, in the long term it simply scares them into reactive mode by triggering avoidance of the topic in question as well as denial.

If you give a large reward to people for doing things they already enjoy doing, they’ll often lose their motivation to keep doing them. 21 22 Think carefully before you increase the salary of an employee who already loves what he does. It might reset his brain to stop thinking of the work as pleasurable and start thinking of it as a tedious task that requires a lot of compensation to keep people motivated.

However, like negative fearmongering, simply handing out rewards does little but encourage “temporary compliance” with a course of action. The fact is, the activity itself has to be rewarding.

This is a subtle but important difference. Research has shown repeatedly that once the rewards stop flowing, people’s behaviors will revert to what they were before. They are extrinsic, not intrinsic, to what commits us to act in certain ways.

However, the survey found that training and goal-setting programs affected worker productivity to a far greater extent than so-called pay-for-performance plans.

The Quick Fix is the immediate reinforcement people need for doing something. If you just entered a casino, immediately hearing the clanging of coins dropping out of a winning slot machine is an example of a Quick Fix. It immediately teaches people that they can win, too— and that they should keep walking in, put some money down, and let it roll. An important thing about the Quick Fix is that people need to get it quickly after they start something. If it takes a while to get the Quick Fix— making it no longer quick— then people won’t connect the reward to the behavior.

The reward also needs to be appropriate for people to keep doing something. A leaderboard of “top employees” isn’t an appropriate reward for an employee who is motivated by supporting coworkers rather than competing with them.

The “Trick Fix” involves intermittent reinforcement. The science behind this goes back to B. F. Skinner, who discovered that rats that were intermittently rewarded with pellets by pushing a lever would push the lever more frequently than rats that were always rewarded. In effect, you’re “weaning” yourself off the reward by getting it when you don’t expect it. So once you feel that you’re on a good path to sticking to something, gradually taper off your reward.

The process should be immediately rewarding to be truly effective.

If you can understand the difference between giving just any reward compared to one that you or someone else truly finds captivating, then you’ll have the power to make change stick.

7. Engrained (Habits). Habits makes doing a task easier and requiring less effort. This comes from repetition.

The human brain is amazingly efficient. It is designed so people can do things without having to think. It rewards people for sticking to routines.

Brains are like cars. Driving them in manual mode takes a lot of awareness and effort. But brains prefer to be in automatic mode. They do this by storing things that frequently occur so they can be easily accessed. Think of it like your computer storing your username and password for a site you visit often. That way, you can log in effortlessly, without thinking, allowing you to concentrate on other things.

That habit then becomes a go-to default behavior. The bad news is that habits— such as addiction to drugs— can be destructive and exceedingly hard to change. The good news is that, with the right efforts, undesirable patterns can be changed. And once people change their habits, strong forces will then be in place to make the new behavior last.

I use the word engrain to describe the process the brain uses to create lasting change. When the brain believes it needs to remember information or a behavior— usually because the thing happens repeatedly— the brain engrains that information or behavior to make it easy to remember so it can do it again.

Because the brain wants to be hyperefficient, it doesn’t stop there. In addition to engraining information about sounds, smells, and sights, the brain also engrains what people do repeatedly. If you take the same route to work each day, the brain encodes this information so you can easily take the same route again. The more you take that route to work, the more it becomes engrained and the less you have to think about how to get to work. The brain follows this pattern across all things in life, even for things that we are not aware of seeing or doing.

The secret to making things engrained in the brain is based on this repetition: repeating behaviors, especially if it can be done every day, in the same place, and at the same time, will teach the brain that it needs to remember this behavior to make it easier to keep doing it. It will engrain this behavior.

One of the secrets to this is repetition. This can be enhanced by doing things at the same time in the same way.

People can pair similar behaviors together so that if they get themselves to do one thing they can easily do, then it will make them more likely to do the other thing that is hard to do. For example, a person might have trouble motivating himself or herself to go for a daily run but can pair this with something he or she already does on a daily basis, like putting on shoes.

Think about it. Because we already put shoes on every day, it is already engrained in our brains. Without much effort, we can substitute the typical work or casual shoes we put on with running shoes. Because running shoes are automatically paired with running, we find it increasingly easier to run. I call this a magnetic behavior because doing one behavior (putting on running shoes) can be a magnet that causes another related and desired behavior (running) to occur.

Sticking with that easy-to-do routine that has led to his success in the past helps him follow through and reach similar success in the future.

To learn a new behavior, researchers found that animals need a stimulus (or a trigger), a response (the behavior), and then a reinforcement (a reward that would make the animal want to do it again).

So why doesn’t conditioning (or habit science) work to create lasting behaviors? If conditioning were the only solution needed for behavior change, then why would this book spend only a few pages of the Captivating chapter teaching you about conditioning?

Obviously it’s because I don’t think it’s the only solution. And neither do most scientists in the field of psychology. In fact, many psychologists think the field of behaviorism is dead. 10 Why? First, people aren’t caged animals, so the research on conditioning that was done on animals often doesn’t apply because people’s minds and lives are more complicated than animals. Second, not all behaviors are the same. There are different types. Each type of behavior requires a different set of forces to change it. Captivating is one tool, but we need more than one tool in our toolkit to make behaviors stick.

Take going running a few times a week. You can’t use conditioning to make that a “habit,” because it will never be a quick, automatic, and unconscious behavior. People have to consciously go through a number of steps to go for a run. When is the last time you realized you had gone for a run without thinking about it?

Although individual parts of this process could become habits— like a few minutes in the middle of the run when the body is automatically moving and the mind begins to wander— the larger process is not a habit.